Tennis for More Than Two

- Sheeva Azma

- Jul 4, 2021

- 9 min read

Updated: Feb 6, 2022

Diversity in video games is profitable, but it is not catching up as fast as the evolving world. Why?

William Higinbotham had one job: to prove that a recovering atomic bomb scientist could still be relevant in a new generation that preferred peace and love.

He who developed the timing system for the first atomic bomb, Higinbotham wrote to his daughter after witnessing the Trinity test, “As you know, it was when I saw the first nuclear test on July 16, 1945, that I determined to do what I could to prevent a nuclear arms race.” Higinbotham co-founded and chaired the Federation of American Scientists and moved from the plutonium-scorched deserts of New Mexico to Upton, N.Y., to seek redemption at the newly christened Brookhaven National Laboratory. Part of his goal at the site, which had recently interned Japanese-Americans during a time of ”race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership” and provided rehabilitation to wounded soldiers of WWII, was to figure out how to apply the science and technology that wiped out Hiroshima and Nagasaki for peaceful purposes.

In 1958, Higinbotham was tasked with creating an exhibit to feature the instrumentation division’s work. Having led the group since 1951, Higinbotham would have known that dryly displaying sensors and circuit boards just wouldn’t cut. So, to “liven up the place … and convey the message that our scientific endeavors have relevance for society,” he and technician Robert Dvorak developed and assembled Tennis for Two, an interactive exhibit where two players play a simulated game of tennis using a knob and two buttons in front of a cathode ray tube.

“Tennis for Two” was literally and figuratively a smashing success, becoming a precursor to Atari’s Pong, the first “truly successful commercial arcade video game.” Gaming has evolved a lot since its early days, moving from the halls of science into devices with the computing power to send a man to the moon and back that could also fit into your pocket. But what about the people who game and those who make them?

The demographics of gaming have changed since their origins and have only accelerated since the early 2000s: in 2006, females represented 38% of gamers; by 2019, that increased to an estimated 46%. Over 50% of PC gamers are women, who prefer Role-Playing Games (RPG), while men seem to prefer First-Person Shooters and Massively Multiplayer Online (MMO) PC games. People of both sexes play video games but men are more likely to call themselves “gamers,” according to a 2015 Pew study.

The old guard that started gaming as far back as the eighties, when Ataris were in vogue, have soldiered on into adulthood and even retirement. An AARP survey found that older women play video games more often than their male counterparts: 53% of female respondents over the age of 50 say they play video games every day, compared to 40% of males.

Another avenue where gamers have become a more diversified group is in terms of race and ethnicity. The 2015 Pew study found that while white, Black, and Hispanic people were all equally likely to say that they have played some type of video game, 19% of Hispanic and 11% of Black respondents self-identified as gamers, compared to 7% of white respondents. Furthermore, A Nielsen study reveals that 10% of gamers are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ), and they spend more on video games than their straight counterparts. They are more likely to be console gamers and prefer simulation games.

With this surge of the new guard in gaming, gamers of all backgrounds are looking for more inclusive gaming experiences. A 2019 study by game maker EA showed that players want more inclusive games. In the study, 56% of participants said that game devs must create more inclusive games, celebrating people from all backgrounds to provide unique gaming perspectives.

As gamers demand more inclusive games, the industry is slowly making progress. Take “The Sims 4” for example, the latest iteration of arguably “the most inclusive game ever.” The game allows characters to choose from over 100 different skin colors and play with LBGTQ identities. Characters can also choose from a variety of careers, regardless of gender. Over 20 million PC copies of “The Sims 4” were sold by February 2020, shortly before the pandemic, making it the most best-selling game of the entire franchise. Unlike “The Sims”, the first-person shooter game “Overwatch” has a fixed number of playable “heroes” but makes up for it by elevating prominent non-white and LGBTQ characters.

“Gaming is a really powerful way to educate people,” Gay gamer Ed Nightingale told BBC regarding the impact of including LGBTQ characters in video games. “When you're playing through a game and not just watching or reading it, you are actively involved in it and therefore actively involved in a character that is so different from yourself - that has really great educational benefits." Indeed, as the Washington Post writes, increasing representation in video games can help gamers feel “seen.”

Two additional, shrewd ways of righting past wrongs are remastering old games and pairing them with upgraded hardware. As Twitch streamer AreolTheJinx noted about Pokemon Red and Blue, which was first released in 1998 for the Nintendo Game Boy, “I’ve been playing Pokémon since the old days. Once they remade the Red and Blue games and you could play as a girl, I got super excited… then, when they came out with the [Nintendo] 3DS and I could be a Black girl, I almost cried. I’ve been playing this game my whole life, and I can finally be myself.” In addition to games becoming more representative of the people who play them, gaming consoles are also becoming more inclusive of persons with disabilities. Xbox has developed an Adaptive Controller that has customizable buttons, delivered in accessible packaging that could be opened by teeth, and features ports that allow disabled games to plug in external devices.

Research shows that diverse game dev teams make more money. Diversity is good for companies’ profitability, according to a 2018 report by McKinsey and Company. This just reinforces the fact that increasing diversity in game dev is a win-win-win: for gaming execs, game devs, and gamers. COVID-19 has only served to further reinvigorate the video games industry, with the BBC calling online gaming “a social lifeline.” Faced with the prospect of staying at home, whether due to shelter-in-place orders, unemployment, or other changing life circumstances, gamers took solace in video games. Total U.S. video game sales increased by 27% in 2020, with consumer spending across video game hardware, content, and accessories reaching a new record at $7.7B. Mobile gaming also broke records in the pandemic, capturing 59% of the gaming market share worldwide by 2021. Our remote COVID-19 world has led to the rise of small-time content creators and entertainers who livestream or talk about video games on platforms such as YouTube or Twitch, creating a vibrant consumer subculture as well.

There is much talk about creating a “new normal” as the world slowly inches back from pandemic-related devastation, but beyond the top 0.1% of games mentioned above, is the gaming world at large reflective of our reality or our imagination of what it could be? To put it in another way, who is allowed to envision such realistic or hypothetical worlds? Who gets to benefit from the modest improvements and radical reimaginations of gaming that so many now rely on for community and sanity?

The most recent edition of the Developer Satisfaction Survey carried out by the International Game Developers Association and Western University in Ontario, Canada, suggested “a large overrepresentation of people identifying as white” and “a large underrepresentation of those identifying as black and those of Hispanic/Latinx origins”

The modal game dev respondent constructed from the results of the IGDA survey was a straight, 36-year-old American male who is white or multiracial with white. He was more likely to be married but childless and had obtained a university degree that was either somewhat relevant or directly relevant to game design and/or development.

To the game dev industry’s credit, one area in which the playing field is more level is in gender identity. LGBTQ game devs are actually overrepresented: 5.6% of Americans self-identify as LGBTQ yet 21% of respondents to the IGDA survey, over half being US-based, reported being homosexual, bisexual, or ‘other’; about the same proportion as of the UK.

In other areas, though, game devs remain less diverse than the gamers they serve, and there remain gaps in character representation. What’s more, old cultural habits of misogyny and exclusion persist. They persist in competitive gaming, game dev teams, and gaming culture at large.

The obvious reasons why the diversification of gamers has been slow is a combination of cost, hardware, and software access (not every company has their in-house accessible consoles like Xbox), in addition to discriminatory culture. On the developer side, there are significant educational and professional bottlenecks towards the diversification of the games industry.

Peeking under the hood though, the gaming industry has to be singled out for a lack of accountability measures, discriminatory cultural norms, and toxic practices such as “crunch”, a period of mandatory overtime in a game’s development cycle. During the COVID-19 pandemic, game devs find themselves even more burned out and perhaps exploited due to their love of video gaming. As game dev union leader Emma Kinema told Ars Technica, "The vast majority of game workers are in the industry because it's our dream job, and working on games is our passion… Unfortunately, that passion can open us up to exploitation by our bosses, because we are simply grateful or content to have the job we have.”

One could argue that the toxic game dev culture also gives rise to toxic gaming culture. When game devs’ contribution to a company’s bottom line is valued more than their mental health or their moral integrity, game devs run out of creative license to come up with collaborative ways of gaming that provide a more inclusive experience or develop safeguards that prevent the harassment experienced by gamers. Game devs, who remain predominantly white and male, are less likely to have firsthand experience of gaming-related harassment.

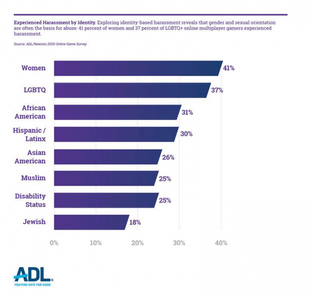

Toxic gamer culture can be most acutely seen in the hostile nature of multiplayer gaming especially when voice chat is on, including harassment based on identity characteristics. According to a 2020 report by the Anti-Defamation League, 68% of online multiplayer gamers aged 18-45 in the U.S. experienced more severe abuse, including physical threats, stalking, and sustained harassment. 41% of females and 37% of LGBTQ respondents, respectively, were harassed based on their gender and sexual orientation. About one-third of Black, and Hispanic players experienced harassment, as did a quarter of Asian-American players and disabled gamers. Gamer culture’s notorious hatefulness may dissuade historically marginalized groups from participating in multiplayer gaming experiences: the ADL reported that “28% of online multiplayer gamers who experienced in-game harassment avoided certain games due to their reputations for hostile environments, and 22% stopped playing certain games altogether”.

However, this new generation of more diverse game developers and gamers is hitting back. There have already been several cases where women in game development teams are litigating and protesting for their rights in these industries. Women and minorities are not only fighting for their rights and recognition in video games culture and industry, but they are also forging their own communities and groups as well — groups like Black Gamer League and Black Girl Gamers. It’s also clear that both game devs and gamers are demanding that every gamer plays as themselves: 87% of respondents in the IGDA survey held diversity within game content as “somewhat important” or “very important”. This will require decision-makers in the gaming industry to diversify their staffing choices, marketing campaigns, and creation of characters when making new games.

The ADL also surveyed preferred systemic-level actionable items to combat harassment, which included blocking certain players from joining their team (60%) and the ability to “push to talk” or mute other players on voice or text chat (58%). It also suggested that “federal and state legislators and executive branch agencies should strengthen and enforce laws that protect targets of online hate and harassment.”

Furthermore, game dev is an industry known for its creativity and innovation. Because games are a product of the game devs that make them, it’s important to make sure the talented game devs from historically marginalized or non-traditional backgrounds that are hired are supported once they’re hired. It can be difficult to promote diversity in an environment without putting the proper social and leadership strategies in place to ensure that all game devs can thrive in the workplace.

Without these changes, game devs will continue to protest the toxic culture in which they work — even walk out of their jobs at blockbuster game makers such as Riot Games (developer of League of Legends), as they eschew an unfair culture that is too physically and emotionally draining to be sustainable. As game dev Nathan Allen Ortega told TIME Magazine, “Every game you like is built on the backs of workers.”

When William Higginbotham and Robert Dvorak built the first video game, they were just trying to entertain visitors of a bygone era: racial segregation in public accommodations was commonplace until the Civil Rights Act of 1964; the Stonewall Riots that birthed the gay rights movement did not happen until 11 years later, and only in 1990 did the Americans with Disabilities Act get signed into law.

The gaming industry that Higginbotham accidentally created has given us one smashing hit after another, but to keep the rally going, it is time for a new generation of players, game devs, and game execs to return serve. The future of the game depends on it.

Alex Ip contributed research to this article.